New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is becoming a practical opportunity for farmers to earn income from carbon, especially on lowerproducing or erosionprone land. The core opportunity is registering eligible post1989 forest (or regenerating native bush) in the ETS so the farm can receive New Zealand Units (NZUs) as trees grow and store carbon.

To qualify, forest land generally must be at least 1 hectare in blocks, capable of reaching 5 metres in height, with sufficient canopy cover and no large gaps, and must not have been forest on 31 December 1989 (or must have been deforested between 1990 and 2007). Farmers can join either as standard “averaging” forestry or as permanent forestry, which locks in longterm tree cover in return for longterm carbon storage. There are emerging limits on new exotic forests on higherclass land, and all legal owners or rightsholders must consent, so checking titles, leases and LUC classes early is important.

Registration involves creating ETS and NZ Emissions Trading Register accounts, mapping eligible forest with digital files, and providing a landuse “story” using aerial imagery, maps and planting records. Many farmers engage forestry consultants to assess eligibility, model carbon sequestration using MPI’s default tables, and prepare economic analysis across different carbonprice scenarios.

For most farm forests, NZUs are “revenue account property”: units earned are generally not taxed when allocated but are taxable when sold, with no GST on sale or purchase and often no cost base to deduct. “Lumpy” carbon income needs careful tax and cashflow planning, making early conversations with a rural accountant essential, especially as policy settings and registration deadlines may tighten.

See below for our full article

Christmas trees, farming and the ETS

In the office, our Christmas tree has gone up and this brings to the increasing volume of questions about the ETS from farmers and its potential application. Outlined here are key aspects of the scheme and how it can be integrated into your farming business.

New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) lets farmers earn carbon units (NZUs) from eligible forest on their land, but it has specific rules on what counts as “forest land” and how to register.

How ETS works for farmers

The ETS puts a price on greenhouse gas emissions and rewards carbon sequestration in eligible forests with tradeable New Zealand Units. As a farmer, your main opportunity today is registering qualifying “post1989 forest land” or certain erosioncontrol plantings and planting on low productivity land so you can receive NZUs as the trees grow.

Using your farm to earn NZUs

On farm, you can typically use forest that was not forest land on 31 December 1989 or was forest on 31 December 1989 and was deforested between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 2007 – and is:

Planted or regenerating native bush

At least 1 ha in blocks

Has the potential to reach 5 m height

Has the potential for the canopy to reach an average of width of 30 metres

Does not have gaps greater than 15m on canopy edges of perimeter trees or clear gaps greater than 1 hectare within forest areas.

From 2023, new post1989 forests usually earn units under “averaging”, unless they are enrolled as permanent forestry, which commits the land to longterm forest cover in exchange for more longterm carbon storage.

There are also emerging limits on new exotic ETS forestry on certain higherclass farmland, so it is important to check your Land Use Capability (LUC 1-6) class and any cap that may apply.

You (or your entity) must also either own the land or hold a registered forestry right or lease, and everyone with legal interests (for example multiple owners) must consent to the ETS registration.

You then take on ongoing duties: submitting emissions returns, keeping records of planting/harvest, and notifying MPI if ownership or land use changes.

Application process and proof required

The basic steps are:

Decide what land is eligible and whether to join as standard or permanent post1989 forestry.

Create an NZ ETS online account and an account in the New Zealand Emissions Trading Register, then apply to register your mapped forest land.

Provide a digital map (shapefile) showing the exact forest area, plus titles, legal descriptions and owner details for each property.

To prove eligibility, MPI expects a “story” of landuse history, which can include dated aerial imagery, satellite images, farm maps, planting records, seedling invoices, or other documents that show the land was nonforest before 1990 and that forest has since established.

You may also be asked for evidence of resource consents (or why they were not needed), and for copies of forestry right or lease documents where relevant.

More information and forest consultants who can help

Many farmers use consultants to assess eligibility, prepare maps, and manage ETS obligations. Examples include:

AgriIntel, which focuses on assessing onfarm ETS eligibility, especially regenerating indigenous bush.

Forest360, offering ETS joining guides, landuse assessment and fullservice forest and carbon management across New Zealand.

PF Olsen, which provides feasibility studies, forest establishment, and ETS advice to forest owners nationwide.

Forme Consulting Group, an independent forestry consultancy working with small forest owners and larger entities across the country.

During an assessment by a consultant, the land and forest is reviewed and mapped for land use, historical and environmental factors. This may require a field assessment and data collection by drone which is used for data analysis and GIS mapping. An ETS forestland assessment would be completed with the findings and an economic analysis be completed with the calculation of returns and an annual cashflow assessment based on the carbon sequestration analysis.

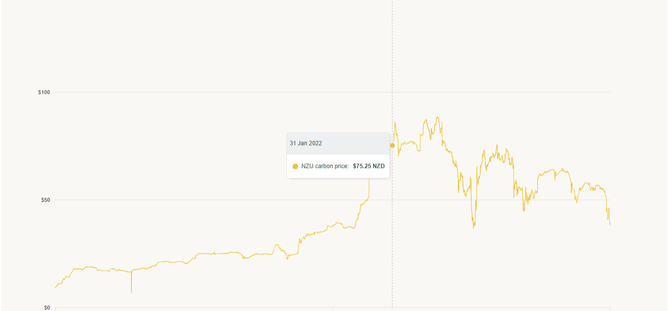

The Carbon sequestration would likely use the default carbon tables (available on MPI website) which is designed for less than 100 hectares of post-1989 forest. A return on investment would be calculated in tonnes of carbon per hectare with the value of 1 tonne of carbon equal to one NZU - One NZU is equal to one tonne of carbon stored. The return on investment would generally be based on three price scenarios over the remaining sequestration period for the forest. Indicative prices scenarios could include prices at these levels.

Pessimistic $30/NZU price floor,

Current spot price $38.50/NZU

Optimistic $160/NZU

Below - Carbon price graph from 2016 to November 2025

Other sources of information include Regional councils and MPI’s climate change team can also point you to local ETSsavvy advisers if you want someone close to your district.

For more information the MPI website has a wealth of information along with the carbon sequestration tables and application process on this website - https://www.mpi.govt.nz/forestry/forestry-in-the-emissions-trading-scheme

Practical Case Study

Here is a case study of how carbon farming can be integrated into working farms:

Ngāti Awa Farms Ltd (mixed farming with dairy units)

Perrin Ag’s “Case Study 5: Ngāti Awa Farms Ltd” covers a mixed enterprise with two dairy units, a drystock block and existing forestry, and discusses options such as replanting radiata, establishing natives, and riparian planting in the context of ETS eligibility and longterm carbon strategy.

The full PDF is available here: https://www.perrinag.net.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Case-Study-5_Ngati-Awa-Farms-Ltd_full-final_compressed.pdf.

Registration timing and “initial” NZUs

Post1989 forest land can generally be registered in the ETS at any time, as long as it meets the eligibility rules and was first established after 31 December 1989. However, you can only earn units from Mandatory Emissions Return Periods (MERPs) that are still current or future at the time your land is registered; once a MERP has finished, you cannot go back and claim NZUs for that past period.

For example, the 2018–2022 MERP closed on 31 December 2022, and participants had until 30 June 2023 to file returns and receive units for that period; if your forest was not registered in the ETS by the end of that MERP, you cannot now claim those “backdated” units.

The current timetable is:

2023–2025 MERP: covers 1 January 2023 to 31 December 2025, with returns due 1 January–30 June 2026.

2026–2030 MERP: covers 1 January 2026 to 31 December 2030, with returns due 1 January–30 June 2031.

What this means for a farmer

To receive an “initial” allocation of NZUs for your existing post1989 forest, you must lodge a complete ETS registration so the land is in the scheme before the relevant MERP you want to claim for has ended; otherwise, you miss out on units for that whole period.

After registration, you can claim NZUs either through the mandatory emissions return at the end of each MERP, or earlier via a Provisional (voluntary) Emissions Return to bring unit earnings up to the current year within that MERP.

Some commentators note a proposed cutoff of 31 December 2027 for lodging complete post1989 forestry applications to access some current ETS forestry settings, so it is worth highlighting that policy settings and deadlines may tighten and farmers should confirm dates before relying on them.

The tax implications of carbon credits

Carbon units (NZUs) have real tax consequences for New Zealand farmers, so any ETS strategy needs to line up with your accountant as well as your farm plan.

When NZUs are taxable - For post1989 ETS forestry (the typical farmforestry situation), Inland Revenue treats NZUs as “revenue account property”.

That means:

Getting NZUs allocated by the Crown for forest growth is not taxable in the year you receive them; tax generally arises when you sell or otherwise dispose of the units for value.

When you sell NZUs, the sale proceeds are usually taxable income to the farm business, regardless of whether the forest itself sits on the capital or revenue side of your balance sheet.

If you simply hold your forestearned NZUs (and do not sell them), current rules for forestland NZUs mean there is usually no income tax effect yeartoyear while you hold them.

However, if you use NZUs in more complex arrangements (for example, trading units not linked to your forest, or entering financial contracts), different financialarrangement or businessincome rules can apply, so specialist tax advice is important.

Deductions, surrendering units and GST

Where NZUs are sold, there is often no tax deduction for “cost” if those units were originally allocated to you for free as post1989 forestland NZUs, so the full sale amount can be taxable.

If you later need to buy NZUs back (for example, after harvest and deforestation, or to exit the ETS), the purchase price may be deductible or recognised under specific “replacement NZU” and timing rules, but the detail depends on your exact situation.

For GST, NZUs are usually treated as a financial service, which means no GST output is charged on the sale of NZUs and no input GST can be claimed on their purchase, even if the farm is GSTregistered.

Because ETS income can be “lumpy”, general farming tools like the income equalisation scheme and forward tax planning may still be relevant to smoothing overall taxable income from forestry and other farm operations.

Practical points

We emphasise that selling NZUs is taxable income and should be budgeted for like milkcheque income or livestock sales.

For farmers interested - talk to a rural accountant who understands ETS,

Read through IRD’s 2025 guidance “Income Tax and GST – forestry activities registered in the Emissions Trading Scheme (IS 25/13)” and its fact sheet for detailed rules.

For post1989 forest on your farm, the key timing rule is that you only earn NZUs from the date your land is actually registered in the ETS, and only for emissions return periods that are still open.

And in a newsflash today, Rabobank has announced it is partnering with a company which specialises in restoring indigenous forests in a bid to generate voluntary carbon credits for farmers through planting on lower-producing farmland.